Two thousand years ago, a Judean man lived and taught in a place ruled by the Roman empire. His final week has been analyzed, dissected, praised, and reflected on for centuries. Theology–an entire religion—formed in relation to his life and his death. According to the records left by his friends and followers, his last days took place around the time of the Jewish Passover feast, a celebration of liberation from a previous domineering empire. The prophet, healer, and teacher heralded by some as the Messiah succumbed to the most notorious symbol of Rome’s empire: the cross. Yet three days later, the tomb where followers lovingly buried his body was empty.

The story of Jesus is told now through the history of conquerors and victors. Two thousand years later, we read through churched eyes. But before Easter, what did his followers make of this “holy week?”

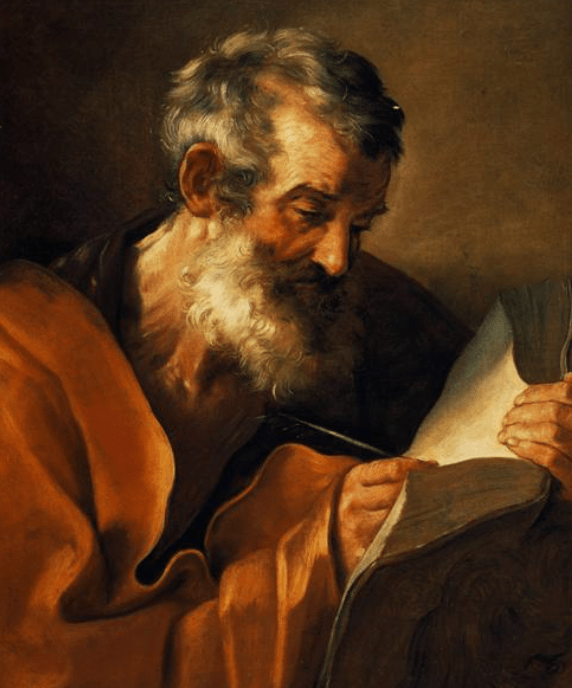

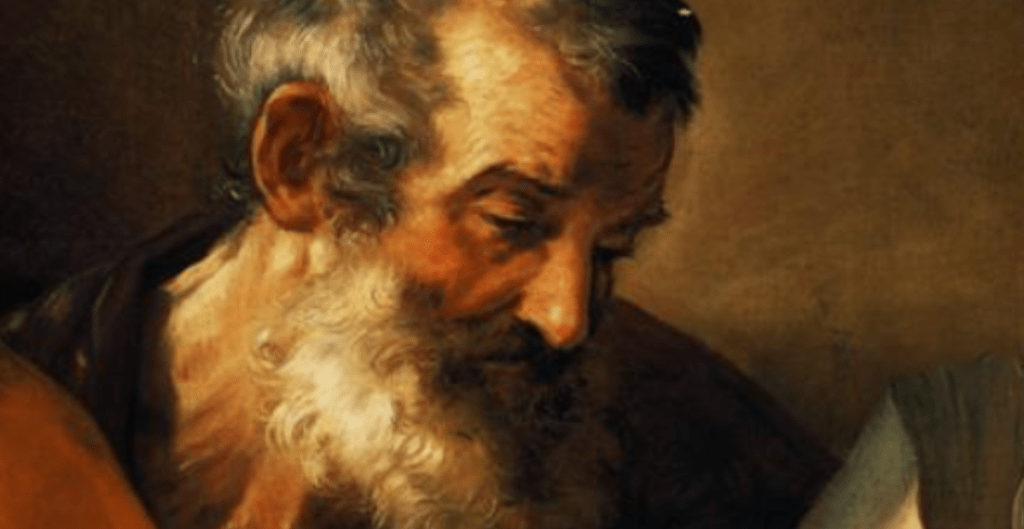

In our tellings of these stories, we will use the book of Mark, the earliest gospel account from which the other synoptic gospels draw. Mark was written around 70 CE, soon after the Judean war during which the Temple was completely destroyed. This was a brutal, violent war which crushed the Judean revolters and carried the precious Temple emblems, like the Torah scroll and Menorah, away as bounty (Borg and Crossan).

It is in the shadows of this devastating trauma that Mark’s narrative unfolds. Originally, his story ends with the empty tomb. The women, as we recall, find the stone rolled away. But in Mark, they run away in fear, and the narrative ends. A few centuries later, someone added the final few verses.

Shadows of war, memories of death, symbols of violent oppression, an empty tomb. These images, symbols, stories continue to sing across time and tradition, and we close our eyes and try to sing back. No one knows the words, but we find the ancient melody familiar. Welcome to Holy Week.

Leave a comment