Theological Background by Kristen

Elizabeth O’Donnell Gandalfo argues that our common inheritance is not corruption but vulnerability. It is our vulnerability—our fragility, precariousness, and nakedness—that drives us toward self-protective, egotistic behaviors that are the root of sin and violence. This is a theological anthropology, an approach to understanding the human person and the meaning of the belief that we created in God’s image.

I find shifting theological anthropologies at work in the Book of Mormon. At times it seems that writers corroborate a nineteenth-century portrait of original sin. Patriarchal images of God and consequential mirrors in society appear, like now, to be operative. But over the course of the record, the different civilizations seem to struggle over definitions of meaning and value. There is not always equanimity about what it means to be a human being, to live a good life, and to be in relationship with life and/or the divine.

Part of the struggle, at least for the editor, goes back to the first few chapters of the record where we experience Lehi’s dream. The prophet dreams an iron rod and a straight and narrow path. To his dream he begs his children listen, extrapolating meaning which to him is obvious:

And he did exhort them then with all the feeling of a tender parent, that they would hearken to his words, that perhaps the Lord would be merciful to them, and not cast them off; yea, my father did preach unto them. And after he had preached unto them, and also prophesied unto them of many things, he bade them to keep the commandments of the Lord; and he did cease speaking unto them

1 Nephi 8:37-38

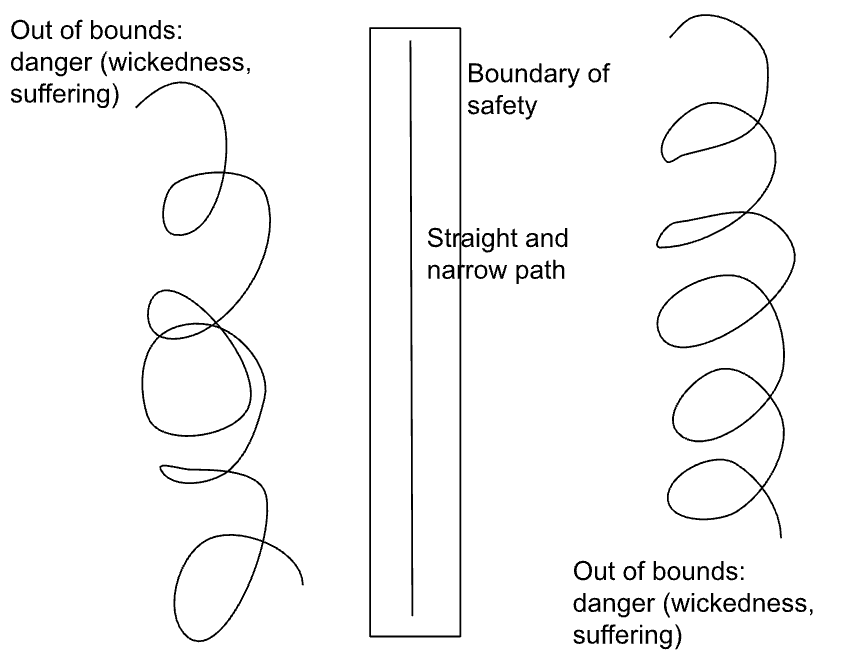

The rod and the path mean a great deal to Lehi. To him, it seems they are symbols of the law, righteousness, and safety. This tradition is passed from father to son in the prophetic tradition, and the keepers of the faith continue living into this theological understanding. We see prophetic exhortations following Lehi’s plea to hold to the rod, by which he means adhere to the law set out for the safety and protection of God’s people. This adherence, for Lehi and his followers, begats safety and prosperity. Deviation is misery and condemnation. The theological paradigm looks something like this:

Just a few chapters ago, Zenniff rehearses a tradition which attempts to justify war:

Now, the Lamanites knew nothing concerning the Lord, nor the strength of the Lord, therefore they depended upon their own strength. Yet they were a strong people, as to the strength of men.

They were a wild, and ferocious, and a blood-thirsty people, believing in the tradition of their fathers, which is this—Believing that they were driven out of the land of Jerusalem because of the iniquities of their fathers, and that they were wronged in the wilderness by their brethren, and they were also wronged while crossing the sea;

And again, that they were wronged while in the land of their first inheritance, after they had crossed the sea, and all this because that Nephi was more faithful in keeping the commandments of the Lord—therefore he was favored of the Lord, for the Lord heard his prayers and answered them, and he took the lead of their journey in the wilderness.

And his brethren were wroth with him because they understood not the dealings of the Lord; they were also wroth with him upon the waters because they hardened their hearts against the Lord.

And again, they were wroth with him when they had arrived in the promised land, because they said that he had taken the ruling of the people out of their hands; and they sought to kill him.

And again, they were wroth with him because he departed into the wilderness as the Lord had commanded him, and took the records which were engraven on the plates of brass, for they said that he robbed them.

And thus they have taught their children that they should hate them, and that they should murder them, and that they should rob and plunder them, and do all they could to destroy them; therefore they have an eternal hatred towards the children of Nephi.

Mosiah 10:11-17

As Bryan Gentry wrote recently, this sort of strategy isn’t isolated to the Book of Mormon. Yet the veracity of the claim, that every single Lamanite is indoctrinated in an absurd tradition of hate and vengeance and that this is the civilization’s defining quality, becomes more and more difficult to uphold. Indeed, it may face its fiercest struggle in the reality of the Nephite division that happens at the end of Mosiah’s record and into the first chapters of Alma. Despite a long legacy built on carefully protected traditions, something happens:

Now it came to pass that there were many of the rising generation that could not understand the words of king Benjamin, being little children at the time he spake unto his people; and they did not believe the tradition of their fathers.

Mosiah 26:1

What makes children believe in, follow, and uphold the “traditions of their fathers?” What makes Lamanites willing to take on their parents’ battle? We could ask the same of Arabs and Jews, as David Shipler does, or of Sunnis and Shias, or a thousand other configurations of prejudice, hate, and resulting violence. This is not to exonerate the Lamanite tradition (or the Nephite tradition!) but rather to wonder on paper whether the stories we tell about each other, even the stories told about people thousands of years ago, tell us the truth as much as they tell us about ourselves and our own fears, worries, and hurts.

Across the line of faith, the straight and narrow path bounded by God’s law, the community Alma carved into being with his very life is ruptured by his own son. The dream of beloved community, of a generation that will keep the fires burning, is torn apart in front of the parent’s eyes. The rupture, we read, is significant enough to be a cause of political anxiety. We often tell the story of Alma and the sons of Mosiah as wayward children brought lovingly back. This is part of the rod paradigm, where the way is strictly bounded and defined within those bounds. These young ones are collected by an angel’s care and their transformation is complete. But the language of departure and return—boundary and out of boundary—fails to capture the depth of what happens here. The rupture, the deviation from the line, is woven into the tapestry of the people and the stories that unfold.

What does it mean, for young Alma, to be created in God’s image? What does it mean for his path to wander in and out of bounds? How does a story of rupture and repair, of healing, shape the subsequent narrative?

Ideas for Play

Contributed by Kristen

- Read the Book of Mormon storybook!

- Watch a Book of Mormon video

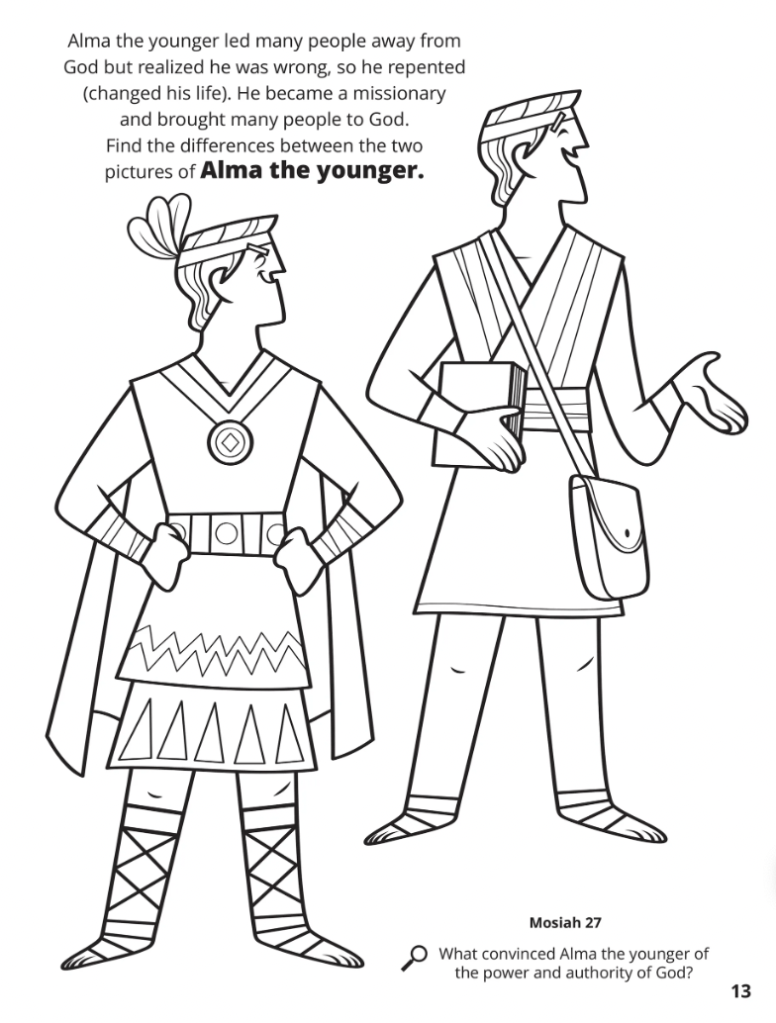

- Alma the younger coloring page

- What does it mean to be created in God’s image?

- Watch this video

- Read I Am God’s Dream

- What does conversion mean?

- Watch this video

- Is repentance like healing? Like weeding a garden? Why?

Artwork

Poetry

‘New Day’s Lyric’

by Amanda Gorman

May this be the day

We come together.

Mourning, we come to mend,

Withered, we come to weather,

Torn, we come to tend,

Battered, we come to better.

Tethered by this year of yearning,

We are learning

That though we weren’t ready for this,

We have been readied by it.

We steadily vow that no matter

How we are weighed down,

We must always pave a way forward.

*

This hope is our door, our portal.

Even if we never get back to normal,

Someday we can venture beyond it,

To leave the known and take the first steps.

So let us not return to what was normal,

But reach toward what is next.

*

What was cursed, we will cure.

What was plagued, we will prove pure.

Where we tend to argue, we will try to agree,

Those fortunes we forswore, now the future we foresee,

Where we weren’t aware, we’re now awake;

Those moments we missed

Are now these moments we make,

The moments we meet,

And our hearts, once all together beaten,

Now all together beat.

*

Come, look up with kindness yet,

For even solace can be sourced from sorrow.

We remember, not just for the sake of yesterday,

But to take on tomorrow.

*

We heed this old spirit,

In a new day’s lyric,

In our hearts, we hear it:

For auld lang syne, my dear,

For auld lang syne.

Be bold, sang Time this year,

Be bold, sang Time,

For when you honor yesterday,

Tomorrow ye will find.

Know what we’ve fought

Need not be forgot nor for none.

It defines us, binds us as one,

Come over, join this day just begun.

For wherever we come together,

We will forever overcome.

Music

Leave a comment