Contributed by Kristen

Shortly after both of my children were born, I remember at least one overwhelming moment of intense anxiety as their tiny little bodies nestled so close and so completely to mine. This is what absolute dependency looks like, my anxiety throbbed. They are entirely reliant on you. And in a mystery of life known the world over, in birthing them I was reborn. Our lives are intertwined so permanently, yet with such fragile precariousness. We are so achingly vulnerable. The tears flowed in those early moments cradling their precious bodies, both in exhilaration at their hard-won being and in a strange sort of bittersweet sorrow that thus they are ushered into the world. This is it, I wanted to say, the frightening descent, the uncertainty, the tug and hollow, and the sure embrace. The smell of me is your lifeline, my darling. I am all you have, and I am so terribly insufficient. And as the days and the months and then the years pass, I see how true it really is. We are all just walking each other home, as Ram Dass says, we are all each other has. We are terribly dependent. We are so truly, fully, terribly dependent.

Jennifer Banks writes that Western philosophy has been and remains obsessed with the concept of death. Death is the great end, the thing we are born to prepare for, the looming specter on the horizon which animates all meaning. But what if, she argues, we shift the tables. What if death is not the primordially important and existentially meaningful thing. What if birth is.

I have been mulling over this idea in various ways since giving birth radically reoriented my entire being. I have been grappling with the Christian story, both professionally and otherwise, for as long as I can remember, struggling with elements of the story that I can’t quite hold. But something inside of me buzzed awake a couple of weeks ago as I rocked my infant, his nose too congested to comfortably sleep on his back, and thought about the story of Jesus coming to the Americas.

In some ways, the story seems a perfect parallel to his ministry in Jerusalem. He says, more or less, what we would expect him to say. Having been trained to expect the importance of a church, we nod at his administrative functions. But something happens in the Americas that ought to radically shift our focus. Something happens that entirely reorders and orients his ministry in the Americas and to the world. Echoing a scenario in the New Testament, Jesus calls the children to him.

Having dramatized the setting, let me pause here. Readers of the Book of Mormon know that children will feature prominently in the remainder of Jesus’ visit. I have read several interpretations and responses to this fact, most of which offer an interpretation along these lines: Jesus focuses on children because he wants to 1) heal them from the trauma of what they have just lived through and 2) strengthen them to establish the church and live faithfully. Extrapolating from here (we are keen to “liken the scriptures!”) I think of a religion professor I once had who often said that the purpose of the covenant path is to keep us in line “until we are safely dead.” This is sort of an “armies of Helaman” approach, or what Paulo Freire calls a “banking model” of education. We need to inoculate our young people, fill them up with knowledge and protection so that they will be prepared to live faithfully, to fight the battles awaiting them. We are ensuring the next generation. Jesus, then, is strengthening the children to ensure the next generation.

I am sympathetic to this interpretation. Especially from the perspective of parents reading the text, I see it. I get it. How, I hear interpreters asking, do we ensure our children’s safety? How do we ensure they will stay where they will be happy? I hear Lehi asking the same question, I see his vision and interpretation of the iron rod. I feel the weight of the longing for sure ground, for absolutes, for a firm enough foundation. I feel, acutely and deeply, the fear. It is born so achingly of love. The smell of me is your lifeline, my darling. I am all you have, and I am so terribly insufficient.

But when I return to the story, I see my own projections. I see my fears echoed in the interpretation I place upon it. The resurrection of Jesus is not a triumphal hymn of transcendence. It is a lullaby. Jesus is not bypassing mortality, having overcome it, he is returning in solidarity. The difference between these things means everything to me. Jesus calls the children not because he wants to ensure that his church will survive for another generation, but because he aches for the vulnerability of these wounded innocents. What losses have they known? What destruction have they witnessed? Who did they cry out for at night? In calling the children, Jesus calls the vulnerable to the center of the narrative. So, of course, Jesus calls all that we try to disguise, to bury, and to protect. Jesus calls the children because this is his mission: birth. Life. Solidarity with our vulnerability. The establishment of a church is a second order concern. Its function is to serve the first.

The story is a circle. It begins with a dream of a girl and her child. The birth is a birth as banal and ordinary as millions of others. The pain, the blood, the sweat, the woman’s body. He is born hungry and cold, like every one of us in the history of the world. He is born with flesh. He dies between thieves, a cruel and humiliating death but no more so than many millions of others the world over. His life is a human life. But then, he comes back. What do we make of this? Why does he come back? And why does he visit the Americas? We could decide that it is because he has triumphed. He comes to say that mortality is beneath his heel. The final victory is won. The problem—human sin—has been dealt with. This is what I might call the “Easter” Christ, or the transcendent Jesus. The problem is, I just don’t think this is it. This is a linear arc, a triumphalist arc. Instead, Jesus retains the marks of flesh. Instead, Jesus calls the children to him and weeps for their woundedness. Instead, Jesus prays.

The story begins with a dream of a girl and her child. A lullaby, that first sleepless night, the star.

Death, agony, and then birth again.

This is the radical reorientation of the Christian story. Not death, but birth. Not forever life, but forever birth. Incarnation, God in flesh, Jesus calls the children. The problem Jesus deals with is not human sin. It is, as Elizabeth Gandalfo says, human vulnerability. Gandalfo quotes Nicaraguan mother Idania Fernandez: “‘Mother’ does not mean being the woman who gives birth to or cares for a child; to be a mother is to feel in your own flesh the suffering of all the children, all the men, and all the young people who die as though they had come from your own womb.” Mother Jesus calls the children. In calling the children, in centering them in this narrative, Jesus shifts the entire thrust of the Christian message. Not victory over death, but solidarity with life. The children are not just a future generation of adults. The children are a representation of our human vulnerability.

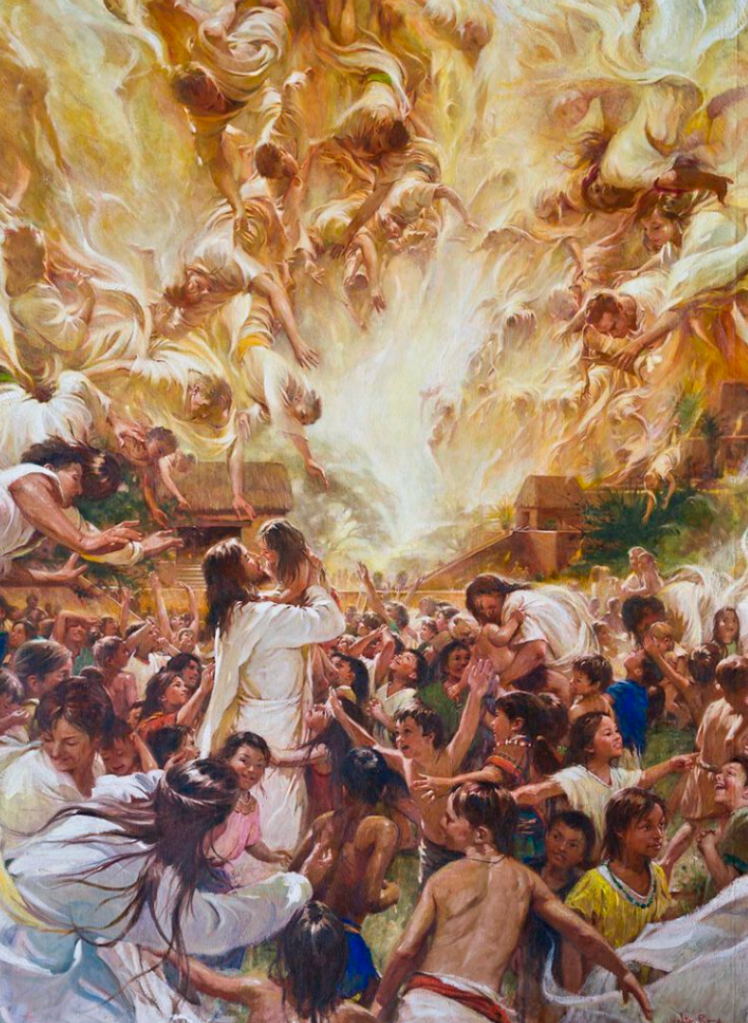

And he spake unto the multitude, and said unto them: Behold your little ones. And as they looked to behold they cast their eyes towards heaven, and they saw the heavens open, and they saw angels descending out of heaven as it were in the midst of fire; and they came down and encircled those little ones about, and they were encircled about with fire; and the angels did minister unto them. (3 Nephi 17:11-30)

Behold your little ones. Behold your littleness. Behold your fear, your longing, your dashed hopes, your broken heart, your weary body. It is so beautiful, I wanted to sing to my children as they blinked and nursed and slept that first living day, it is so terrible and so beautiful. There is so much I do not know. There is so much I am afraid of. Oh, but the flowers. The birds. The mountains. The trees. Child, welcome here. I love you. Forgive me. I’m here.

We trail off, humming a lullaby, gazing out into the unknown. Tomorrow is a mystery. All is well.

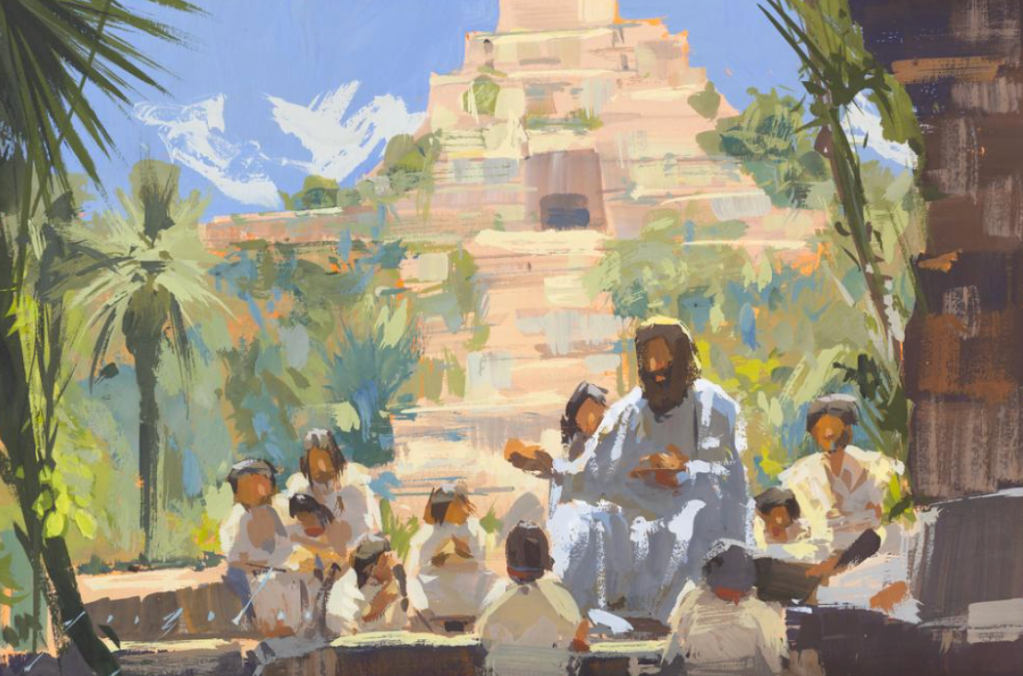

Artwork

Compiled by Caroline

Poetry

Compiled by Caroline

As a Child Enters the World

by John O’Donohue

As I enter my new family,

May they be deligthed

At how their kindness

Comes into blossom.

Unknown to me and them,

May I be exactly the one

To restore in their forlorn places

New vitality and promise.

May the hearts of others

Hear again the music

In the lost echoes

Of their neglected wonder.

If my destiny is sheltered,

May the grace of this privilege

Reach and bless the other infants

Who are destined for torn places.

If my destiny is bleak,

May I find in myself

A secret stillness

And tranquillity

Beneath the turmoil.

May my eyes never lose sight

Of why I came here,

That I never be claimed by the falsity of fear

Or eat the bread of bitterness.

In everything I do, think,

Feel, and say,

May I allow the light

Of the world I am leaving

To shine through and carry me home.

Music

Compiled by Caroline

Leave a comment