Contributed by Kristen

This week, we’re exploring how we tell the foundational stories of the Latter-day Saint people.

This whole milk and honey project started with a few moms talking about how to tell our kids stories that honored their intelligence and dignity as people. We wanted to tell stories that didn’t talk down to children and that honored complexity and difficulty without tokenizing challenges. We wanted to tell hard and painful stories, because we wanted to tell our children stories that are true. We’ve tried to create resources that flesh out religious and spiritual stories with history, philosophy, theology, art, music, and poetry with places to enter from wherever you find yourself in your spiritual life, and that continues to be our goal.

So this week, we’ve invited some friends and experts to discuss different approaches to the Joseph Smith story, including the different versions of Joseph’s prayer experience, a contemplation on theophany itself, and an essay reflecting on the importance of particular stories even from outside the faith. We hope you’ll come explore with us.

Ideas for Play

Contributed by Kristen

- Read this version of the story for kids

- Create sacred spaces. What makes a place special to you? Where would you go to say a special prayer?

- Maybe make a collage of images that feel special and sacred.

- Visit a forest if possible. What makes it feel special?

- Look at pictures of the sacred grove in New York.

- Talk about theophanies (appearances of God) that we know of. What questions do you have? What questions do your kids have? What is the same or different about Joseph’s experience?

- Read accounts of Joseph’s vision together and discuss them. What stands out to you? How do they make you feel? How would you tell stories about a spiritual experience? Have you ever tried to write one down?

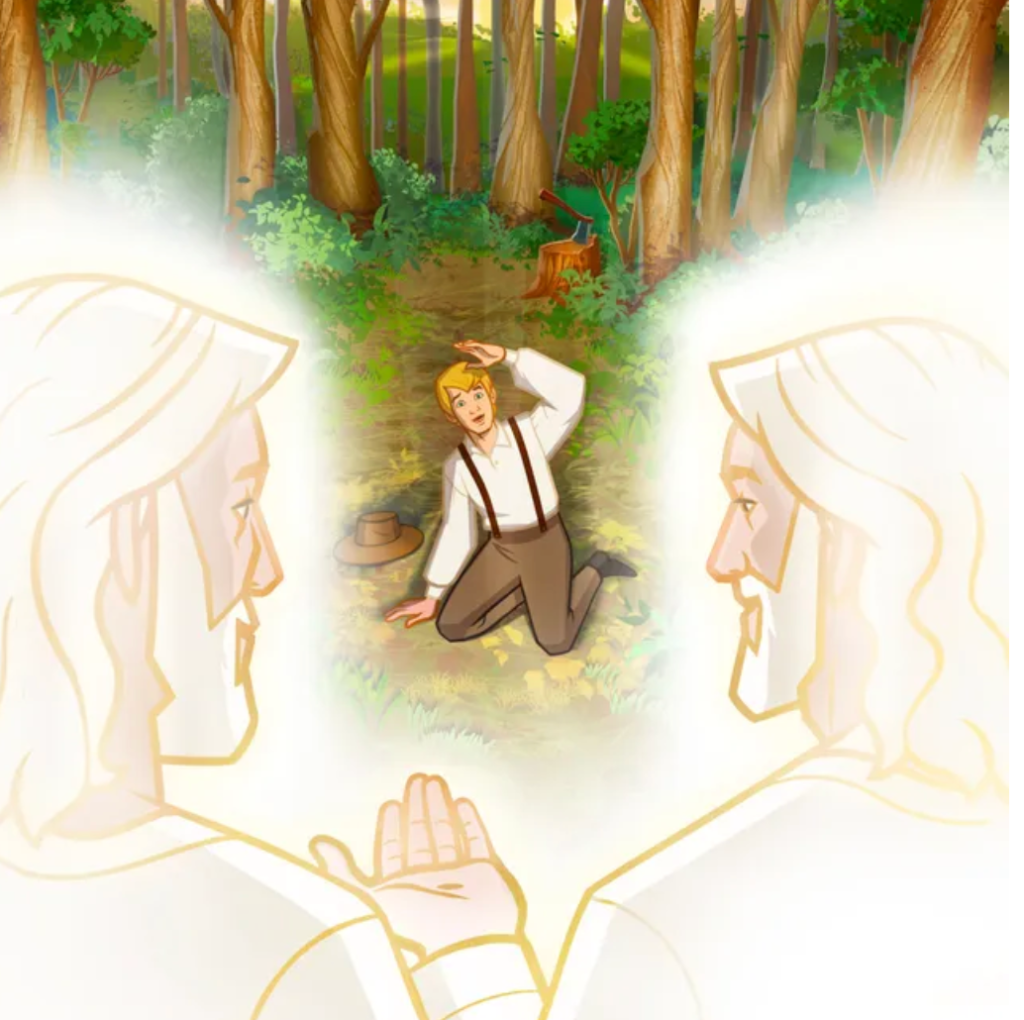

- Look at as many different artistic interpretations of the vision as you can. How do different artists imagine this event?

Artwork

Compiled by Caroline

Warren Floyd Luch, 1990

Versions of Joseph Smith’s First Vision

Contributed by Greer Bates Cordner

Greer Bates Cordner is a Ph.D. candidate at Boston University. Her primary area of research is American Religious History, with Global Christianity and Mission as a secondary area. Greer also holds a Master of Theological Studies degree (Boston University) and a B.A. in History (Brigham Young University). She is a mom to three young kids, all of whom were born during her doctoral program, and who put her academic and gospel studies into perspective with their questions, hugs, and prayers.

One of the hardest parts about history—including Church history—is that it is almost never possible to recapture events once they’ve passed. Warning historians about various fallacies to avoid, David Hackett Fischer pointed out: “A sense of time is not a simple thing. . . . It is difficult enough in this day and age for a person to imagine that there really was a past and that there will be a future. But even when that lesson is learned, one must master the idea that there are many different pasts and futures. . . .”[1] Narratives of past events can vary from each participants’ perspective, or from telling to telling (even from the same person). It becomes the job of the historian, or the storyteller, to select which narrative to relay in any given telling, and to determine which details to include to suit the purpose of the story in that moment.

Although it’s impossible to capture every facet of every perspective of the past all at once, the best storytellers embrace the flexibility of the narratives they recount, leaving room for curiosity about all the other ways someone could tell the same story.

The idea that there are “many different pasts” can widen Latter-day Saints’ views about Joseph Smith’s first vision. Only one account of Joseph’s encounter with God in the woods has reached the status of scripture for Latter-day Saints, but the Church has begun taking steps to make other versions of Joseph’s experience more widely available. Each of these first vision reports seems to have a different focus, and details of the narrative vary across the accounts. Even though he was telling his own story, using his own words, Joseph Smith could never fully peg down something that was, ultimately, not just a story; it was an experience, and it was infinitely complex.

Looking at reports about the first vision from other members of Joseph’s family, even more details emerge that color the experience further. Personally, I love the report that Joseph’s brother, William, gave many years after the fact. In an interview that multiple newspapers later published, William answered a question about what prompted his brother to seek divine guidance about which church to join. “Why, there was a joint revival in the neighborhood between the Baptists, Methodists and Presbyterians,” William replied.

. . .[And] a Rev. Mr. Lane of the Methodists preached a sermon on “what church shall I join?” And the burden of his discourse was to ask God, using as a text, “If any man lack wisdom let him ask of God who giveth to all men liberally.” And of course when Joseph went home and was looking over the text he was impressed to do just what the preacher had said. . . .[2]

William’s account of the first vision is not a story about an individual; it is a story about a community. The most common version of the first vision casts Joseph’s neighborhood and its heated revivals as a setting in which a character (Joseph Smith) faced a crucial question, made an inspired discovery in scripture, and experienced a revelation. But in William’s story, the neighborhood and the revivalists are themselves key characters in the central action. William remembers the Rev. George Lane—a major figure in the history of the Genesee Annual Conference of early 19th century American Methodism—as the person who nudged Joseph Smith to pair James 1:5 with the search for a church, and to take its invitation seriously.[3] In this telling, revivals were not a source of confusion but of inspiration. William’s account shows that someone other than Joseph Smith believed that God would answer sincere pleas for guidance, and that Joseph gained strength from another’s faith.

By highlighting the influence of other people in the circumstances for the first vision, William Smith reveals another piece of the “many different pasts” into which the restoration fits. Joseph Smith met God in the context of a family, a neighborhood, a system of religious revivals, a Protestant tradition of seeking answers in the Bible, and so, so much more. Although the teenage boy might have been alone when he prayed that spring morning in 1820, the story isn’t only about him. After all, who knows whether Joseph would have “retired to the woods” (Joseph Smith–History 1:14) without the Rev. George Lane?

Keeping flexible boundaries for narratives of the first vision allows room for curiosity about the people and events that make Joseph’s experience so rich.

[1] David Hackett Fischer, Historians’ Fallacies: Toward a Logic of Historical Thought (New York: Harper Colophon Books, 1970), 132.

[2] “Another Testimony: Statement of William Smith, Concerning Joseph the Prophet,” Deseret Evening News, 20 January 1894, 11 (https://newspapers.lib.utah.edu/details?id=1626557).

[3] For more on the Methodist context of Joseph Smith’s first vision, see Christopher C. Jones, “The Power and Form of Godliness: Methodist Conversion Narratives and Joseph Smith’s First Vision,” Journal of Mormon History 37, no. 2 (Spring 2011): 88-114.

Contributed by Sophie Blair

Sophie is a musician, Philosophy student, and researcher in Linguistics.

I am walking down 9th and 9th with four men, two of whom I’ve never met before.

Overall, they are nice men. Two living on the east coast, two on the west. Here on a ski trip. Zach, whose hands and right eye twitch in a friendly, energetic way, tells me he and Daniel met at Berkeley. The other two keep in step, looking toward the tea house; the pottery studio. They’ve never been to Snowbird, but they like the snow.

We arrive at the end of the block and collectively hesitate, as the cold’s pretty pressing. Throughout the night, the conversation’s faltered. A long, slightly pregnant pause, and then a quick, direct interjection, perhaps latching hastily to a thread before.

David, who lectures in cosmology at Princeton, responds after one such pause. No, I don’t know much about Mormons. Wasn’t raised religious; none of us were. I wait before responding, and the silence stretches. Because I know the next interjection, know it carnally.

Are you Mormon? he says.

I breathe out.

Years of lurching. Producing vague, unsatisfactory answers. Because how do you tell them? Him, especially, New Jersey-bred, looking with polite and passive interest at the various eccentricities of South Salt Lake, wondering kindly but with detachment about the typical Mormon life. And how strange, how inconclusive, my own Mormon life has been.

With a bit of evasion I say, my family is.

No one presses me—it’s really very cold—but I plough on, still. The usual logical, irrefutable truths: that I was raised Mormon, that my family and community are devout, devoted. I then launch a bit spasmodically into abstraction, saying bits about Zen and folklore and cowboys, finding myself in moments somehow defending the indefensible while at once abasing it.

We turn, in one relenting motion, back the way we came. I wonder if I’ve left my car lights on; watch Daniel check his watch, then shake his sleeve, nearly imperceptibly, over his wrist. And I wonder, for the hundredth time, how I ought to.

How to structure. How to scaffold. How to explain.

Not in this exact moment, but in others, I have thought about my ancestors. “Ancestors,” a word so common to colloquial Mormonism, so integral to everything. Mine, who I’m assured have bled barefoot in snow, leaving children’s cadavers to wolves, in a Trek of devotion. I wonder briefly what is owed to them—what, in a 30-second encapsulation of a childhood’s religious experience, I can offer them.

Apologies, perhaps.

I think, too, of my Monastic wanderings—Early Morning Seminary and all that, plunging up the Wild Mouse in 4-degree snow. Such a depth of Biblical knowledge, and so young. All of us, apprehending the Christ-myth with casual and quick familiarity. Yes, of course, Jacob 4. The War Chapters. Joseph Smith Translation.

It’s not nothing. And I am here, beyond all that. But even now, this Salt Lake evening, something surges through my skin and up the pavement; something I retain that they cannot. Not simply a singular experience, but a singular Being. I echo the place—the place this is—and still it echoes me. And I cannot deny these things.

To mitigate the silence, I say, you want to hear a story?

We’re back to walking, five abreast, and they say, sure.

I take a breath, because it’s been a long time. And slipping into “Mormon language,” out of practice, takes a moment.

Okay, I say. Uh. Once upon a time,

And I begin. About this little upstart teenager, frightened of his brothers, who’s told by his prophetic father of some Golden Plates. And in the house of this guy Laban, a rich man, who laughs the kid right off the property, how he’s led by the Spirit, not knowing beforehand what he’ll do. How that same Spirit tells the kid go back, go back. And Nephi finds the tyrant, fully armored, passed out there within the palace gates.

And how with Laban’s sword this Nephi slices off his head.

And takes his clothes.

It’s not much, I think. At most, something for these friends to chuckle at, to brush against. Oh weird, they’ll say someday. That one weird Mormon story.

At best, I am a Mormon still in body, not in practice. But my parents, and teachers, and concourses of neighbors told these stories, again and again and again.

They are a part of me. They are my landscape.

And perhaps there’s nothing else to salvage, or to own. These lovely years; communities that cradled me. These friends; these camp nights. Guitar and weeping; Young Women braiding friendship bracelets. Pass-along-cards. Forgiveness.

But still, there is this Folklore. Rich, intertextual, intercultural knowing. Something about freedom, about modern-day Biblical understanding. About taking a dying thing and making it your own. Taking its clothes, and holding them around you.

Sharing, when you can, a story.

These myths are still a part of me. They are my landscape. And I cannot forget them, or reject them. They undulate, with greater and greater force, the more I try to turn away. The indefensible aside.

And perhaps all I can give is this—a story here and there. Telling my children, someday, about Laban’s head. Asking them, what does this mean? What does it offer? What to keep?

Accessing this. Allowing this. Remaining, with awareness, in contact with the language of this. The cruxes; falls. The cadence.

Because what else can I do?

Here, ancestors. Here, world. I tried. I’ll give you this. Here’s one more story for today—I’ll tell it now, and then again, maybe tomorrow.

It’s what I can. It’s how I’ll try to. It’s a start.

Contributed by Kristen

In the language of academic theology, Joseph Smith’s experience in a New York forest was a theophany, an appearance of God.

Theophanies, manifestations of divine in physical terms discernible to human beholders, are the subject of much theological speculation. The concept of God appearing to (let alone speaking or engaging with a human being) is fascinating not least because it rests on a couple of assumptions particular to the Christian tradition:

- There exists a steep hierarchy between the divine and the human (in other words, g the things of God and the things of humans are two totally separate and deliberately non-touchable entities)

- Because of the God/human distinction, the divine takes physical forms only as mediating containers for communication. God may appear as a pillar of fire or a being, but God is not reduced to that fire or that being.

This distinction is part of a long, complex history of metaphysical Christology which itself assumes certain characteristics of divinity. This is muddy territory because we are now talking about an inherited tradition related to the Hebrew Bible but distinct from the emerging Jewish religion and influenced by Greek and Roman philosophical traditions. For patristic thinkers generally, it is assumed that God’s divine nature is entirely distinct and separate from human nature. Indeed, a later theological development now referred to as apophatic theology will propose that God is so transcendentally beyond the realm of understanding that God can only be spoken of in terms of what God is not. God is ultimately beyond any description that could be proposed (God is beyond goodness, beyond wisdom, beyond eternity, beyond love, etc). God cannot be captured even by an infinity of descriptions of God.

Joseph Smith is not an academic theologian. He is not versed in any of the metaphysical theological distinctions that color the term ‘Theophany’ in theological discourse. For Joseph, the divine disclosure is an ultimate and cataphatic Theophany; he believes God is fully revealed and fully knowable in discrete terms.

I love the idea of divine disclosure unsullied by the weeds of academic jargon. Joseph’s experience was a child’s — pure and simple, and radically disorienting. But at the same time, the theological background helps me to see where we as a tradition might unsuspectingly put up blinders, policing God’s ability to be an infinite and diverse God.

So at the end of my musings, I wonder about the boundaries defining God and God’s disclosure. Is a Theophany limited to an encounter between a human and a radically other being of marvelous power? Or could it be that God is diffused in the world, that the world is effuse with God, that the outpouring of divine love overflows from the world to which God is infinitely tied? The theology of Panentheism suggests God in the world, a world bursting at the seams with the presence of God.

Is the rolling river a Theophany? The Amazon rainforest, the lungs of our earth? Does the ocean disclose the divine, or the desert, or the spring buds on the apple tree?

Perhaps it is just metaphor. But I take comfort believing that God’s revelation is not rare but effusive, swelling from the earth like the salmon swimming home: again and again and again.

Leave a comment