Contributed by Kristen

Someone asked me recently if I believe the Book of Mormon is a historical record or a creation of Joseph Smith. I actually feel significant apathy toward the question. That’s not to say I think it’s totally irrelevant and I sympathize with the weight behind it—I recognize that it really matters to people—but I’m just not really captured by the debate. I absolutely see the influence of white, Protestant, 19th century America in the Book of Mormon. I also agree and resonate with my friends Josh and Sarah who write that the Book of Mormon stories are “real stories about a real God who loves real people.” I resonate with this in the same way I resonate with one of my most quoted statements: “all stories are true. Some actually happened” (Sheila S. Otto). I have been moved beyond my ability to narrate by the stories of the Book of Mormon. In many ways, this book shaped and raised me like another mother and it continues to nurture, challenge, and frustrate me as I read with new lenses and questions and pains. I love the stories. I love the people in the stories. Reading it as a literary text, I find great meaning in the practice of close-reading, comparison, and critical theory. For me, attributing the authorship to Joseph Smith just gives the guy way too much credit.

That said, the mystical, magical landscape of its supposed inception does give cause for much head scratching. Some have suggested that this head scratching would be mitigated by our transportation to the mystical, magical climate of the revivalist landscape of young Joseph, where the practice of “scrying” was a common folklore, and that the mythic gold plates make sense in the equally contextualized practice of treasure hunting which set the stage for Joseph’s reception of the plates.

The upkeep of the myth of purity, to my mind, is one of the most effective gate-keeping strategies for the pollination of truth’s fecundity. The iea that Joseph Smith was a “pure” channel for the word of God, a mouthpiece as it were, or that prophets in general are such conduits, turns God into a puppeteer and God’s words into the language of men. Could the Book of Mormon be a work of magic, of 19th century literature and of ancient myth? This is a tall order, I recognize, and I’ll leave this essay with the question open. But as I conclude, I picture once again the final scene of the Book of Mormon.

Moroni sees what the prophecies of women and men the world over have always seen: the world, continuing on. After the calamity, the sun would rise. Tomorrow, a new moon. Winter would come, blanketing this place with snow. Spring would thaw. Soon, no physical trace would remain on the earth. The birds would sing here again, the animals return. The trees would keep the story curled within, passed only to the squirrels skittering on their skin. And one day, there would be people again. The descendents of these who now lay dead know nothing of this battle now scattered on land and water far away. One day, their ancestors would call them home. Is the blood still good?

At the end of the world, Moroni sees the circle of life. Birth follows death, and death birth. Children would come, and fox kits. Salmon would run upstream again, even with no one to greet them, and bears cubs would emerge from their caves in the spring. At the end of the world, Jesus. Life after death, and death after life. At the end of the world, hope. Not for a new world, but a better one. A world where brothers take hands and greet each other by name. A world where wrongs are made right and the past haunts not with agony but with knowledge. A world where the children of every species are safe from harm. A world of life, and death, and life and death again.

He calls to the dust: carry my words, the words of my body which tomorrow will swirl in the wind as you. Carry my words over the mountains and across the sea, over centuries and dynasties and evils again and again. From dust we came, to dust we will return. In every breath of the wind, the voice of the ancestors, calling to the world, settling into the sediments, swirling in every memory.

It gives me hope to imagine that amid its human blindnesses and biases, the Book of Mormon carries forgotten stories and enfleshed prayers. It gives me hope to imagine that God’s goal is not dogmatism and exactness, not puppeteering, but witness to the wide world. I want to live into that witness, expanding the parameters of God’s presence from the gate-keeping terms we apply to God’s voice and role.

To my read, the worship of the idea of a singular, strict covenant path is what destroyed Lehi’s family and eventually an entire civilization in the Book of Mormon. At the end of the world, civilizations apart, there is a child holding stories in his hands. Could the project be not merely restoration of exactness but healing of woundedness? I’m not much interested in the former. But I’m keen for the latter. I’m keen to listen to the earth, to receive stories of those so different from me, to reach across mycelium networks for connection and try, try, try again.

For Littles: Book of Mormon

Contributed by Kristen

Remember when Joseph Smith went to pray in the forest? Remember how he learned something that you and I already know? We know that God loves to listen to little voices. God loves the sound of sparrows, and orangutans, and crocodiles. God loves the music of waterfalls and oceans, the swaying symphony of forests and the jazz ensemble of rainstorms. God loves human voices, too, in their many languages and dialects. God loves the language of those who speak with their hands, and the language of those who don’t speak at all.

And you and I also know that God does not hide from creation. God pops out in the funniest, strangest ways, usually when we least expect it. God dances on mountaintops with sheep and goats and sings with the voices of crickets and angels and speaks to frightened, lonely girls and boys in every corner of the world at any time you could imagine. We know that, but remember that Joseph didn’t know it at first. But he was learning it.

After his experience with God, Joseph was expecting that God would start telling him all the right ways to do and live and be, because isn’t that God’s job? But Joseph was in for another surprise. It turns out God doesn’t really care that much about all the stuff the people around him were arguing about. God wasn’t really interested in telling Joseph exactly what to do and how to live – what would be the fun in that? And once again, God knew something that Joseph didn’t know yet. God knew that the world was much bigger and older and more colorful than Joseph, or the people who made the laws and wrote the books where Joseph lived, imagined.

You see, God knew the story of a hillside close to Joseph’s house. The hillside was tall and rocky and covered in green grass and sprouts and saplings. That was all Joseph knew – I’m not sure he even knew the hillside’s name. But God knew that thousands of years ago, the hillside wasn’t a hillside at all. It was the ground of a great battle where many thousands died. It was a place of sadness and despair, and it was the place where Mormon knelt for the last time to pray. The place of that battle probably had a name in Mormon’s language, but we don’t know it. Maybe it had a name before Mormon’s language, and maybe it had a name deeper than human language at all. We don’t know any of that. But we do know that when Mormon knelt to pray, he also knelt to offer his final hope. He had kept the records of his people with the stories they had carefully written down over the many years of their long history. And that day, he dug a hole in the soil and buried the stories deep in the ground and he asked the Mother earth to keep them safe. Thousands of years passed. The hillside grew and changed. Trees grew in the place of the great battle. Animals lived and died. People lived and died and fought each other and demanded their right to the earth in the language of law and force. No one knew of the stories buried deep in the ground.

No one, that is, but God. God knew. And thousands of years later, when Joseph expected God to do the sorts of things that people who wrote fancy books and drafted fancy laws did, God did something that seemed quite odd. God said, the stories of my people have been lost to the world. But they have never been lost to me. Because I remember every creature, every plant, every living thing on this earth. And if you want to, you can be part of the work of remembering.

That is a little story about where the Book of Mormon came from. There are many pieces and layers of this story. Maybe, if you are like me, you will spend your whole life finding more pieces and more layers. Sometimes it is hard work, and sometimes it is frustrating work. But can I tell you one thing I believe? Here it is: God is a God of remembering. God remembers people who feel lost, and animals who are afraid, and plants who are thirsty. And God remembers stories even when they are at the part where everything falls apart. And my child, God remembers you.

Ideas for Play

- Act the story out! Bury “plates” and then dig them up

- Talk about what you believe about the Book of Mormon

- Does God remember you? How? When have you felt God close by?

- Does God call us to work with them? What does God call you to do?

- Read the final pages of the Book of Mormon together and Joseph Smith’s testimony witnessing the plates.

- Get out a map of the world and play a “finding and remembering” game. Take turns pointing to a place on the map. Then “zoom in” (with the help of a phone or computer) and tell a fact/ story about the place you’ve found. Does God know about all of the stories of the world?

Artwork

Compiled by Caroline

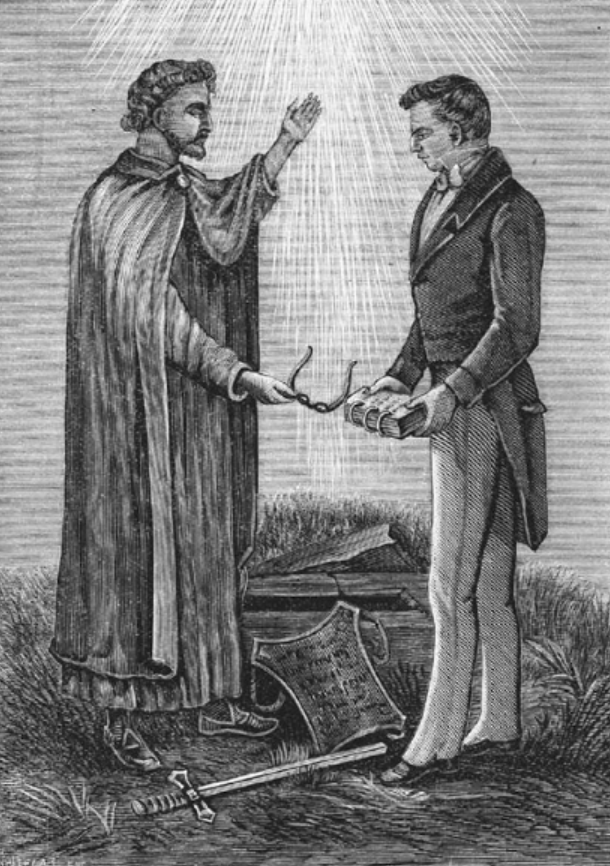

A 1893 engraving by Edward Stevenson of the Angel Moroni delivering the Golden Plates to Joseph Smith in 1827. From Reminiscences of Joseph, the Prophet (Salt Lake City: Stevenson, 1893)

Leave a comment