Contributed by Greer Bates Cordner

Greer Bates Cordner is a Ph.D. candidate at Boston University. Her primary area of research is American Religious History, with Global Christianity and Mission as a secondary area. Greer also holds a Master of Theological Studies degree (Boston University) and a B.A. in History (Brigham Young University). She is a mom to three young kids, all of whom were born during her doctoral program, and who put her academic and gospel studies into perspective with their questions, hugs, and prayers.

General Conferences in recent memory have not devoted significant attention to instructing Church members on questions about recognizing whether a visiting spirit is from God or from the devil. For many twenty first-century readers, Doctrine and Covenants section 50 might seem dated—steeped in a world that early Mormons knew, but that fell away over time. The shift from overt charismatic Mormonism to the more staid spiritual manifestations of later years has gotten some scholarly attention, but not nearly enough. (At least, that’s my biased opinion; aspects of that shift are the focus of my forthcoming dissertation.)

However, as much as the historical context for section 50 matters, it’s also worth probing questions about the place of the section in the Church today. Doing so could require readers to recognize and challenge some assumptions, though.

Brief Historical Overview

Matthew McBride has written a fantastic introduction to the charismatic spirituality that surrounded—and existed within—early Mormonism. Although the essay is brief, it hits a few key points: Many of the early Latter-day Saints experienced dramatic manifestations of biblical spiritual gifts, and so did many other American Christians at the time and in the area. Subtle, but present, in McBride’s essay is the fact that Latter-day Saints understood these spiritual gifts as evidence of the “restoration of all things.” Terryl Givens has underscored that point even more thoroughly in his chapter on spiritual gifts in Feeding the Flock: The Foundations of Mormon Thought: Church and Praxis. As Givens (correctly) points out, an outburst of tongue-speaking during sacrament meeting, a miraculous healing, a vision, or a prophetic dream was “controversial evidence for [the] Restoration, according to Mormonism’s first missionaries.”[1]

But as section 50 highlights, spiritual gifts could pose problems for early Latter-day Saints too. McBride summarizes the conflict this way: “[I]t was not always clear which [spiritual] manifestations were inspired and which were spurious.”[2] The idea that some individuals were experiencing “spurious” expressions of spiritual gifts was, in many ways, a question of authority. In 1830, Joseph Smith instructed Hiram Page not to use spiritual gifts “to command him who is at thy head” (Doctrine and Covenants 28:6), laying the foundation for the idea that any revelation that conflicted with official positions by the Church could not be divine.[3]

But there’s another aspect to conflicts between individuals’ spiritual manifestations: Early Latter-day Saints, like many of their contemporary American Christians, truly believed in a rich spiritual realm inhabited by both good and evil spirits. For this reason, exorcisms were not uncommon among early Latter-day Saints.[4]

For most believers at the time Joseph Smith dictated the revelation, the “false spirits” that section 50 identifies as “go[ing] forth in the earth, deceiving the world” were literal entities that carried potent, destructive abilities. The passages instructing Smith and the early Latter-day Saints about how to discern between good/evil spirits would have felt like the kind of urgent information a missionary would need to carry into the field. It was a validation of the reality of evil, but also a measure of protection empowering believers to identify and withstand that evil.

Spirits and the Twenty First Century

The most recent mention of demons that I can find in General Conference addresses was in Ronald Rasband’s October 2018 talk “Be Not Troubled.” There, Rasband mentioned several concerns that people (especially prospective parents) might have about the state of the world, and he retold the story of Elisha and the angelic army. Then he testified that even though believers today “may not have chariots of fire sent to dispel our fears and conquer our demons,” God will always save his children in one way or another.

The “demons” Rasband spoke of here do not come across as literal entities; the phrase seems more to echo colloquial use of the term as a description of personal failings, addictions, shortcomings, etc. Other late twentieth-century mentions of demons in Conference take a similar approach; for instance, the term appears in a letter Stephen Richards quoted about a person’s propensity to drive above posted speed limits.[5] Still other talks use the term to describe scriptural events, like when Jesus cast out demons,[6] or even—in a fascinating talk by Spencer Kimball—as a moniker for the violent armies that massacred the Ammonites in the Book of Mormon.[7] And in 1961, Milton Hunter quoted from a book about early Catholic missionaries to indigenous Americans that used the term.[8]

By and large, public Latter-day Saint addresses in recent years have not treated demons or evil spirits in quite the same way that the early Mormons did.[9]

In many ways, it is not surprising that Latter-day Saint Church leaders in twenty first-century America do not address the topic as urgently as their earlier counterparts did (shown by section 50). And Mormons are hardly alone in this shift away from fixating on the world of spirits. Philip Jenkins has pointed out that “[f]or most Europeans and Americans, anyone holding [current] beliefs [in demons, witchcraft, etc.] must be irredeemably premodern, prescientific, and probably preliterate.”[10] With some notable exceptions,[11] Western Christians of the twenty first century tend not to embrace the same spirit-worldview that D&C 50 showcases from early Mormonism.

But Christianity is not a majority-Western religion in the twenty first century. Demographically, Christianity is a religion of the “global South,” or “majority world,” and represents thousands of cultural perspectives, interpretations, vantage points, languages, etc. that rarely appear in Western-focused analyses of the gospel.[12] And the kinds of Christianity that are exploding across the world are typically charismatic in nature, or steeped in indigenous traditions.[13]

Mormonism, like other Christian denominations, is experiencing a demographic shift away from its traditional Western center. With each passing year, it becomes increasingly important for Latter-day Saints in the United States to ask whether the perspectives of global Saints get enough air time, and, if not, how to seek out and elevate those voices. The parts of the world where Christianity in general, and Mormonism in particular, are growing most rapidly often have different perspectives about spirits. Could D&C 50 strike current-day readers in Kenya, Cambodia, or Kiribati differently than it strikes readers in the US or the UK? And is there room in the Church today to address potential differences in questions about spirits?

I’ll admit that, personally, concerns about evil spirits don’t take up much of my attention; it’s really not part of the culture I grew up in. But reading section 50 invites me to confront three questions that can help me—and other readers—expand our understandings of how the scriptures can work in others’ lives. Those questions are:

1. What might this section have meant to readers at the time/place it was given?

2. What might this section mean now to readers whose worldview differs from my own?

3. What does it look like to be in a church community with worldviews that differ from my own?

[1] Terryl Givens, Feeding the Flock: The Foundations of Mormon Thought: Church and Praxis (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017), 213-256.

[2] See above link to Matthew McBride’s “Religious Enthusiasm among Early Ohio Converts,” in Revelations in Context, eds. Matthew McBride and James Goldberg (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2016).

[3] Givens gives an overview of this kind of conflict in Feeding the Flock, 225-226.

[4] See Stephen Taysom, “‘Satan Mourns Naked Upon the Earth’: Locating Mormon Possession and Exorcism Rituals in the American Religious Landscape, 1830–1977,” Religion and American Culture 27, no. 1 (2017): 57-94; and Christopher Blythe, ““The Exorcism of Isaac Russell: Diabolism and Nineteenth-Century Mormon Identity Formation,” Journal of Religion 98, no. 3 (2018): 305-326.

[5] Stephen Richards, Conference Report, October 1958, 83-86.

[6] See Howard Hunter, “A More Excellent Way,” April 1992.

[7] Spencer Kimball, “The Evil of Intolerance,” Conference Report, April 1954, 103-108.

[8] Milton Hunter, “The Greatest Event in Ancient America,” Conference Report, April 1961, 50-54.

[9] This does not, of course, mean that there no longer exists a belief in these spiritual entities, but it does indicate a shift in the amount of attention the topic receives.

[10] Philip Jenkins, The Next Christendom: The Coming of Global Christianity (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), 176.

[11] It is not always possible to draw clear lines distinguishing fundamentalist/neo-evangelical Christianity from charismatic/Pentecostal Christianity, and the evangelical Christianity that has been making headway in the United States often blurs these lines. For instance, Billy Graham (and his followers) believed deeply in the reality of evil spirits. Graham, and many other American evangelicals, often weaponized discourse about demons—like in Graham’s anti-Islamic rhetoric (see “Evangelicals Stir New Animosity toward Islam,” National Catholic Reporter 39, no. 1 [2003], 24). Belief in evil spirits has also driven many evangelicals’ opposition to the Harry Potter series and Halloween (see Jason C. Bivins, Religion of Fear: The Politics of Horror in Conservative Evangelicalism [New York: Oxford University Press, 2008]). However, despite growing influence, especially in political spheres, many of these more extreme views still have not yet become mainstream in the United States or Western Europe.

[12] Jenkins, The Next Christendom, 17-26.

[13] Jenkins, The Next Christendom, 26-28.

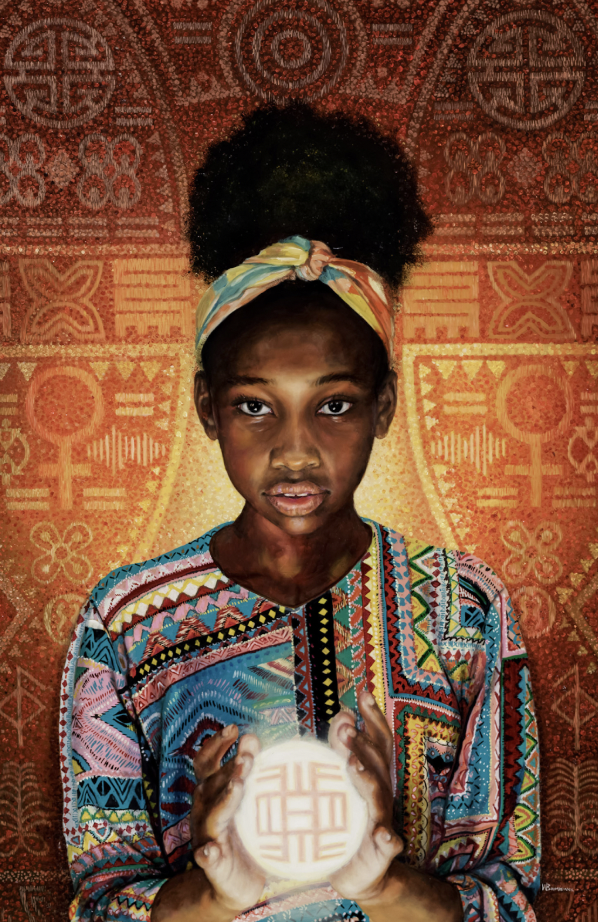

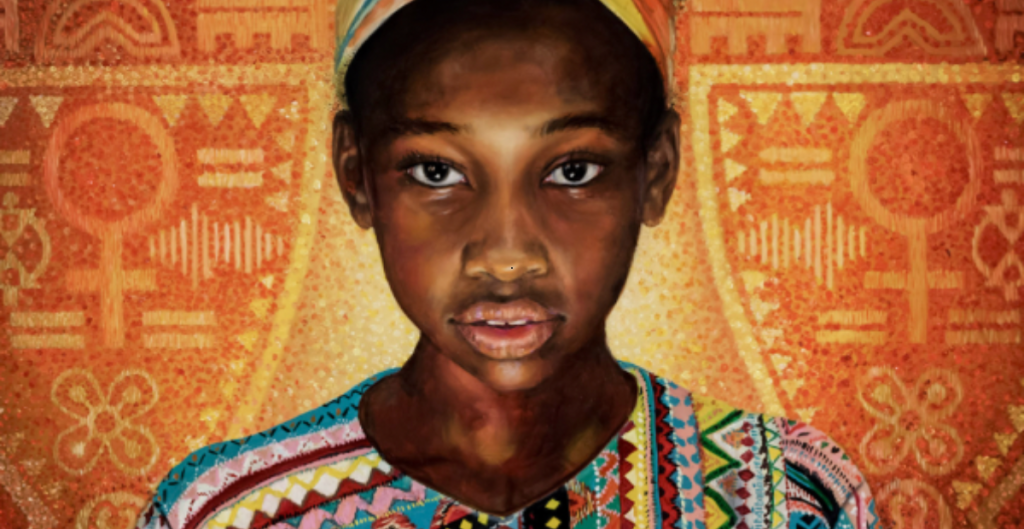

Artwork

Poetry

“Gift”

by W.S. Merwin

I have to trust what was given to me

if I am to trust anything

it led the stars over the shadowless mountain

what does it not remember in its night and silence

what does it not hope knowing itself no child of time

what did it not begin what will it not end

I have to hold it up in my hands as my ribs hold up my heart

I have to let it open its wings and fly among the gifts of the unknown

again in the mountain I have to turn

to the morning

I must be led by what was given to me

as streams are led by it

and braiding flights of birds

the gropings of veins the learning of plants

the thankful days

breath by breath

I call to it Nameless One O Invisible

Untouchable Free

I am nameless I am divided

I am invisible I am untouchable

and empty

nomad live with me

be my eyes

my tongue and my hands

my sleep and my rising

out of chaos

come and be given

Leave a comment